Dr. Tommy Wood, a neuroscientist at the University of Washington, presents a comprehensive discussion on brain health and cognitive function throughout the lifespan. His research underscores the factors contributing to cognitive decline, dementia risk, and strategies for prevention. He highlights that while age-related cognitive decline is often viewed as inevitable, many aspects—such as lifestyle choices and cognitive stimulation—are modifiable and can significantly impact brain health.

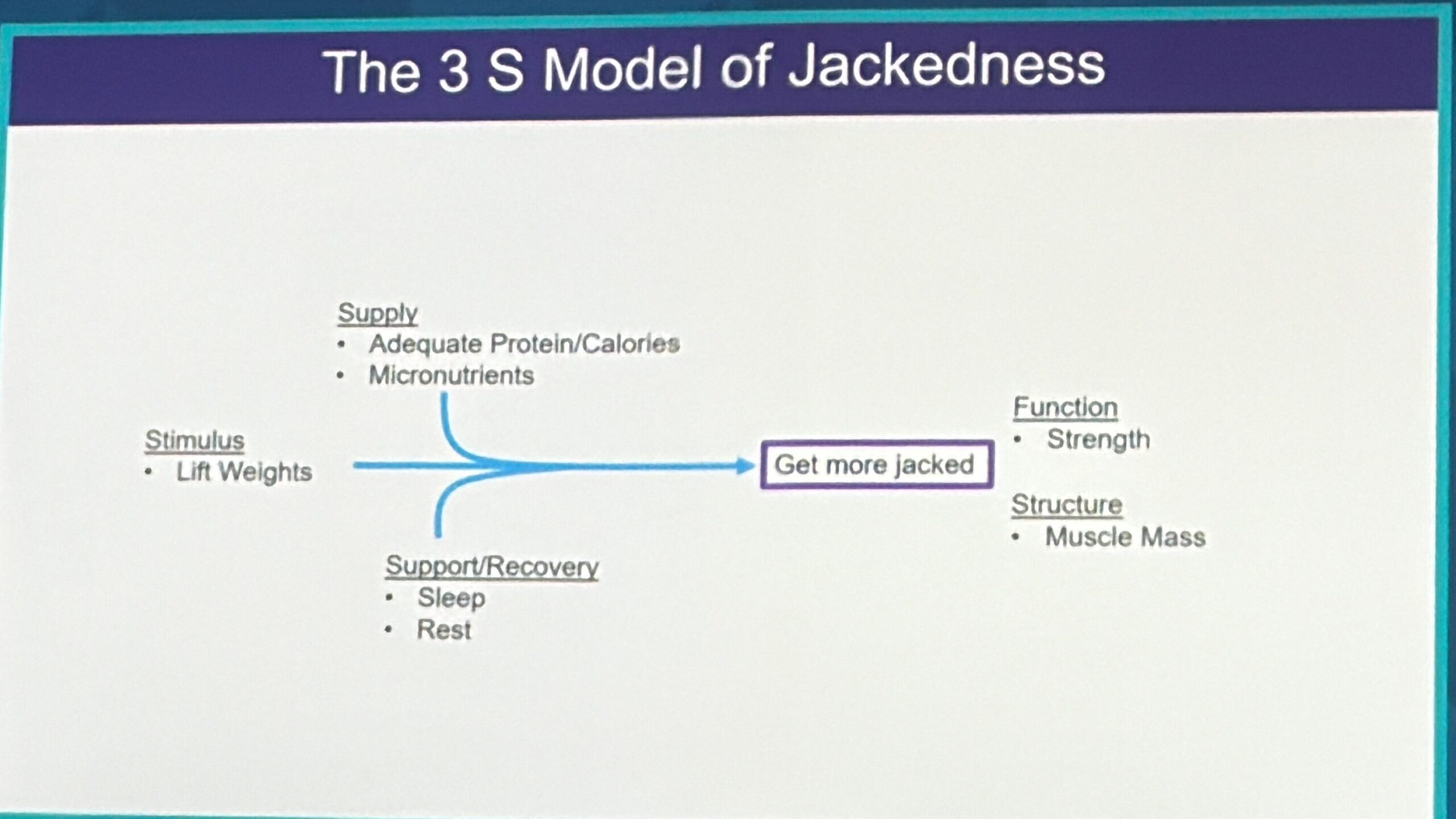

Tommy Wood discusses the intricate relationship between muscle building and cognition, drawing a parallel between physical training and cognitive health. His presentation emphasizes a model he terms the "3S model" of cognitive function, which stands for stimulus, supply, and support.

1. Stimulus:

- Demand-Driven Model: Wood articulates a demand-driven theory of cognitive decline, paralleling the need for stimuli in both muscle building and cognitive functions. Just as lifting weights stimulates muscle growth, engaging in cognitively demanding activities drives brain function. Cognitive stimulation can include education, learning new skills, and social connections.

- Biochemical Changes: When the brain is stimulated through activities that challenge it, various biochemical changes occur, leading to cellular regeneration and improved neuroplasticity, which is crucial for maintaining cognitive health.

2. Supply:

- Nutritional Support: A healthy cardiovascular system and adequate nutrition are critical for both muscle repair and brain health. Important nutrients include protein for muscle synthesis and micronutrients such as B vitamins and fatty acids that support brain function. Adequate blood supply is necessary to deliver these nutrients effectively to the brain.

3. Support:

- Rest and Recovery: Just as muscles require rest to grow stronger after training, the brain needs sufficient downtime (e.g., sleep) to process and adapt to new information. Neuroplastic processes that contribute to cognitive resilience occur predominantly during rest, underscoring the need for a balanced lifestyle that includes recovery.

- Neuroplasticity in Response to Challenge: Wood highlights that the brain continues to adapt even in later life, similar to muscle response to training. Learning new cognitive skills (like juggling or playing an instrument) has been shown to result in structural changes in the brain, particularly in areas associated with those skills.

- Cognition and Aging: His research reveals that just as muscles can atrophy without use, cognitive functions can decline without sufficient stimulation. Engaging in challenging cognitive activities can help maintain or even improve cognitive function into older age.

- Interconnected Systems:

- Cerebral health is interwoven with physical health. Regular resistance training is shown to improve white matter integrity in the brain, which correlates with better cognitive functions, such as executive functioning and decision-making abilities.

- The role of physical activity, particularly aerobic and resistance training, is critical for maintaining cognitive health. Exercise not only stimulates the brain but also promotes better blood flow and nourishes neuronal networks.

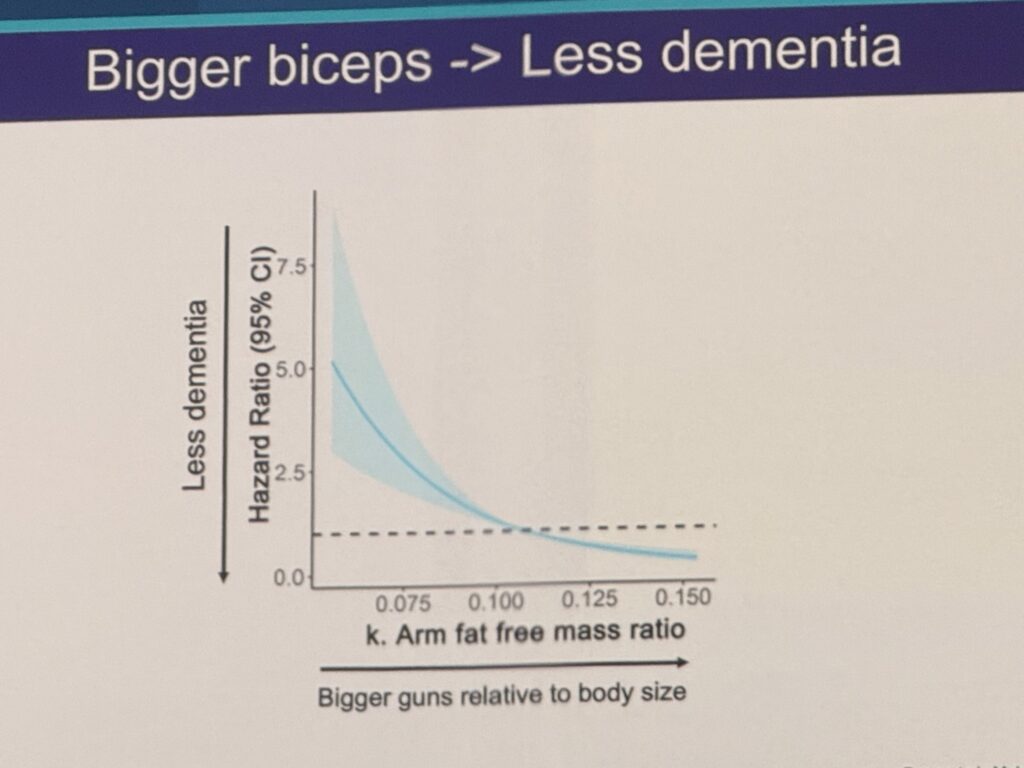

- Wood asserts that many risk factors associated with dementia are modifiable. His findings suggest that a significant proportion of dementia could be preventable by improving lifestyle factors such as nutrition, physical activity, and cognitive engagement.

- The data he references illustrate that maintaining a cognitively stimulating environment, both early in life and well into later years, is pivotal. Individuals with higher educational backgrounds and those engaged in cognitively stimulating jobs tend to have lower dementia risks.

Overall, Wood's lecture advocates for proactive engagement in cognitive activities, better nutrition, physical exercise, and maintaining social interactions as effective strategies for preserving brain health and enhancing cognitive resilience against aging and dementia.

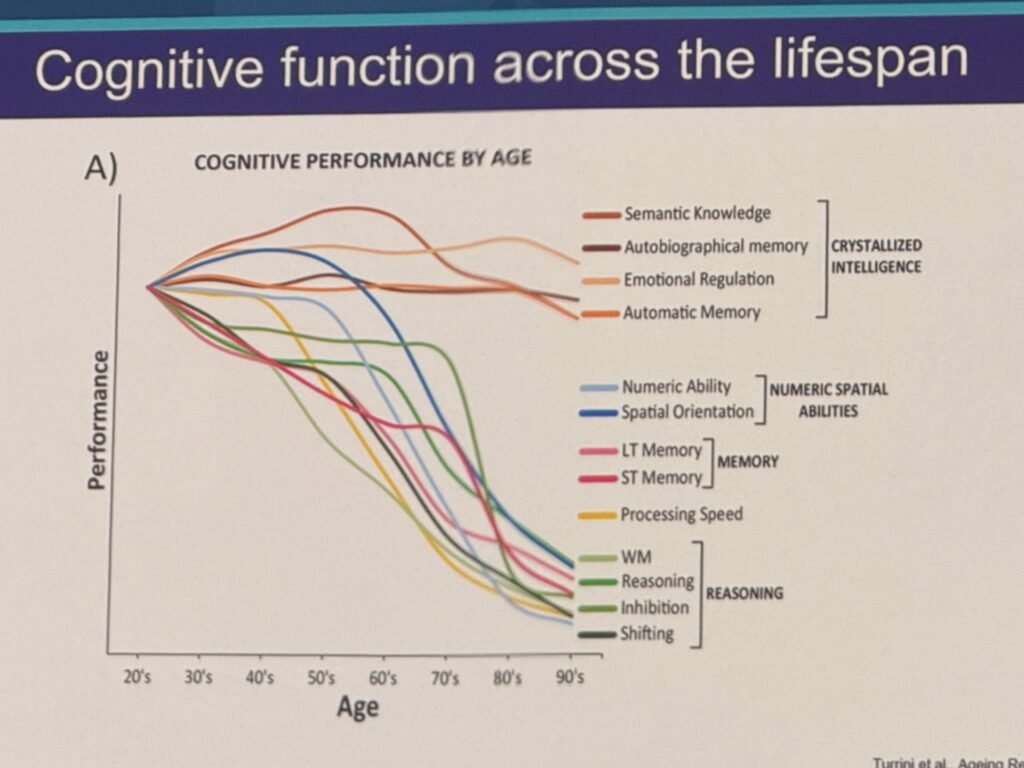

Dr. Tommy Wood discusses cognitive performance and aging, emphasizing that while crystallized intelligence—related to knowledge and wisdom—remains stable or even peaks in midlife, other cognitive abilities like memory, reasoning, and numerical skills decline with age. He notes that this decline tends to start in our 30s and continues progressively, culminating in a higher likelihood of dementia as one ages.

Wood stresses that the traditional view of cognitive function follows a simple trajectory of decline, which he argues is an oversimplification. Instead, he points out that many individuals maintain their cognitive function well into old age, and while there may be an average decline, a significant portion of the population does not experience cognitive deterioration.

He highlights several protective factors against cognitive decline, including education, cognitive stimulation, and maintaining social connections. Engaging in cognitively demanding activities, both in early life and later in life, is crucial in preserving cognitive function and even pushing back the onset of decline. Thus, he argues that proactive steps can be taken to enhance brain health throughout life, suggesting that cognitive decline is not a predetermined fate but something that can be influenced positively through stimulation and lifestyle choices.